Ephesians 2:4-10

Psalm 19:7-10

Luke 10:25-37

What Does God Require?

But he, desiring to justify himself, said to Jesus, "And who is my neighbor?"

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

Last Sunday we reflected on the word of words, Agape,

which is the foundation stone of the Kingdom of Heaven.

St. John the Theologian revealed Jesus to be the Word,

the Logos.

Traditionally,

the most-inner mystery of that Word is that it is God's Real Name,

breathed upon the void,

whose vibration transformed increate matter into our world of beauty and splendor,

unique in all the universe.

The Son of God, the Eternal Word, therefore, is begotten of God,

the instrument and agency of Creation.

With the Fall of Man,

a most

important dimension of that Word unfolds before us,

which is sacrifice, self-giving provision, forgiveness, love.

Jesus tells us that we are no longer slaves but His friends if we will do His commandments.

What is the nature of friendship with Him?

What are His commandments?

He illustrates friendship with Him in the test He lays before Simon bar-Jonah.

In last week's lesson,

He asks,

"Do you love me, not with the brotherly love you have professed,

but with the self-sacrifice you have seen on my Cross?"

In this week's lesson, He illustrates His commandments.

"What must I do to inherit eternal life?" asks an expert in Halakhah, or the Law.

(The words Scribe, Lawyer, Pharisee we should understand to be synonymous.)

He is a Pharisee, the leading group among the Jews who studied and commented on the Law.

When Jesus replies with the Two Great Commandments,

the Pharisee rejoins,

"You have answered right.

Do this, and you shall live."

We see through this brief exchange that at least some Pharisees

agreed that the Law is summed up in two commandments:

love God

and

love your neighbor.

This is not an innovation that comes to us through Jesus of Nazareth.

During the late first century B.C.,

lived two great Pharisees who debated this point:

Shammai,

who often insisted on a strict, literal interpretation of the Law,

and

Hillel,

who often took a more humane view.

In a famous showdown between these two great sages,

Hillel told Shammai that he could recite the whole Law standing on one foot.

"Preposterous!,"

Shammai replied.

"No one can recite

613 commandments

standing on one foot!"

So Hillel,

assuming the crane-like posture and said,

"You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and

with all your strength.

And what is hateful to you do not do to your neighbor.

This is the whole Law."

In this morning's Gospel,

the Pharisee,

accepting Hillel's well-known teaching,

wishes to explore the question further:

"But who is my neighbor?" he asks Jesus.

Certainly this would have been a lively question in an occupied country.

Shammai taught that the Jew should have no interaction with Romans or any other Gentiles.

And this would include Samaritans,

whom Shammai and his followers deemed "not Jews."

Jesus' reply,

which we call the Parable of the Good Samaritan,

is subtle and finely nuanced.

Perhaps we have lost these nuances in our culture of Good Sam RV clubs

and

Good Samaritan Laws.

For it is a bloody and terrible crucible,

asking us to choose between the Two Great Commandments,

between God and neighbor,

and

clarifying the all-important question:

What does God require of me?

"A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho,

and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him,

and departed, leaving him half dead."

Jesus has carefully selected this road for the purposes of his story

(which, by the way, is nowhere near Samaria),

for all who heard it would instantly picture the victim covered with blood.

The road from Jerusalem to Jericho is a barren, rocky road.

Sharp stones would have been seen everywhere.

An unclothed man

(we hear that he is stripped first), beaten nearly to death and thrown down on to this ground would have been bleeding

through several abrasions and lacerations.

The point of the passers-by being priests and Levites is that they

are relied upon to serve at the altar of the Temple.

This is probably the purpose of their journey to Jerusalem.

They are vested as priests and Levites are,

for they are immediately identifiable.

We have no shortage today of paintings or cartoons of these men,

depicted in their fine vestments giving

the victim a wide berth.

I suppose our own mental images are of wealthy people in Manhattan

in the 1930s

dressed in top hat and silver-tipped cane

crossing the street to avoid beggars.

Most often

the priest and the Levite are depicted as being haughty fellows:

their eyes are averted, their heads are tilted back,

with a superior, disapproving air.

But that is not the point Jesus is making.

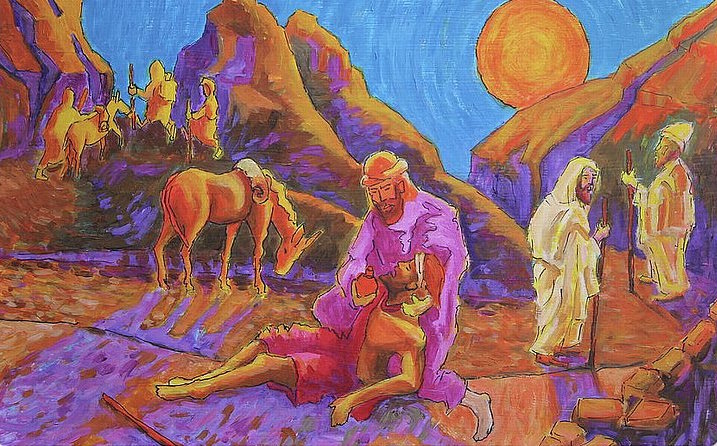

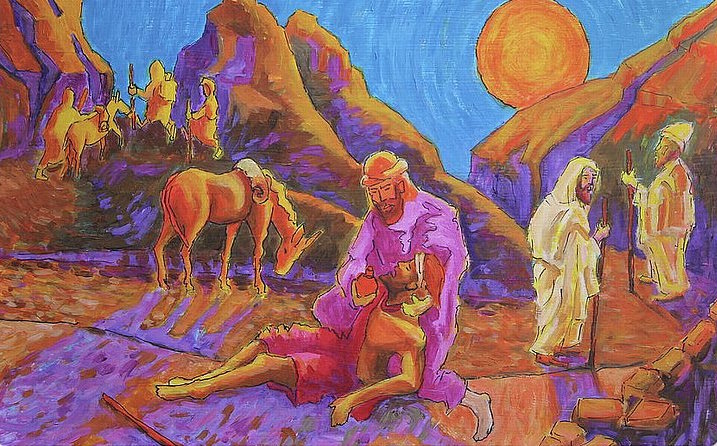

The painting of the Jericho road victim

by Bertram Poole

posted on the

Hermitage website

is bathed in red and purple.

The victim is covered in red.

And

the painting posted on the Hermitage "Spiritual Conferences" page

by Aime Morot

depicts the victim as a pale, near-dead figure,

almost a corpse.

These artists

understood the horrible dilemma that was being set before the priest and the Levite

in Jesus' carefully constructed test.

If they come to the aid of this man,

they will honor the Second Great Commandment, but they will fail in the First.

In their own terms,

they will have done the ethical thing,

but in so doing,

they will have stumbled in their devotion to God.

For in touching the victim,

they will become ritually unclean,

unable

to approach the holy altar of God,

falling down in their rotation.

They will have to wait for time to restore them to cleanness

and

abrogate their appointed obligations to God.

The painting of the Jericho road victim

by Bertram Poole

posted on the

Hermitage website

is bathed in red and purple.

The victim is covered in red.

And

the painting posted on the Hermitage "Spiritual Conferences" page

by Aime Morot

depicts the victim as a pale, near-dead figure,

almost a corpse.

These artists

understood the horrible dilemma that was being set before the priest and the Levite

in Jesus' carefully constructed test.

If they come to the aid of this man,

they will honor the Second Great Commandment, but they will fail in the First.

In their own terms,

they will have done the ethical thing,

but in so doing,

they will have stumbled in their devotion to God.

For in touching the victim,

they will become ritually unclean,

unable

to approach the holy altar of God,

falling down in their rotation.

They will have to wait for time to restore them to cleanness

and

abrogate their appointed obligations to God.

Now, what would be the consequence of ignoring this prohibition,

of ministering to the victim,

arranging for his care,

and

then proceeding to the Temple to complete their priestly obligations?

They would be

excised from the people Israel (we would say, excommunicated).

Moreover, they should expect

a divine decree of death,

struck dead by God,

as those who touched the Ark of the Covenant

without due preparation were struck dead.

You see,

the priest and the Levite are confronted with a terrible choice.

This is not a simple case of indifference to the suffering of others.

It is, rather, the terrible dilemma of choosing between the holy things of God,

an incommensurable category,

and

the love of neighbor,

another incommensurable category.

Which of these most important obligations should you honor?

To render unto God what God requires

or

to render love unto one's neighbor, which God also requires?

It is not so simple as deciding that they are somehow one and the same thing,

for

we can imagine many scenarios in which we might offer sacrificial love

to our neighbor,

which would violate God's moral laws.

So

which one will it be?

You choose:

God or neighbor?

Let us honor the ancient principle

going back at least as far as Origen:

gloss Scripture with Scripture.

One of the points being made in last Sunday's lections concerned

the same dilemma:

giving succor to one's neighbor at the cost of ritual uncleanness.

Jesus has just returned after being among the dead represented by the tombs of the

Gadarenes in Aram.

We might add, "the tombs of Gentiles!"

He has no sooner landed from his trip across Lake Genessaret

when He is touched

by a woman who has hemorrhaged for twelve years.

In this parable,

the woman is an idealized figure,

a kind of (pardon me) "super menstruater,"

enduring an unceasing period of a dozen years.

Impossible for a real-life woman.

The idea is that she renders unclean everyone she touches.

And the point of her interaction with Jesus is that she touches Him.

This is emphasized:

she touches Him.

How often is Jesus touched by one He has healed?

If the shadow of Jesus should fall on someone they are healed.

She touches Him.

From here,

Jesus goes off to touch a corpse,

that of Jairus' daughter,

which is the most egregious instance of ritual uncleanness under the Law.

He has, according to the Law,

separated Himself from God.

Again,

this is a highly stylized scene:

a woman whose menstruation is perpetual

(commanded by the Law to be separated from all other people)

and

a corpse.

In the first century,

anyone hearing this would have labeled it the Parable of the Unclean.

In the Sunday lections before us,

the victim is beaten on the rocky terrain of the Jericho Road

and

is near death.

He nearly combines in his own person the uncleanness of the

bloody woman and the corpse of the dead girl.

His bleeding body lies motionless on the road.

To the priest and the Levite,

and to all hearing this tale,

he is the personification of uncleanness.

We can almost hear the crowd listening to this story saying aloud,

"Don't touch him!"

the way that we watching a horror film would say,

"Don't go in there!"

The entrance of a lone Samaritan into the scene adds new depth to the story.

Followers of the sage Shammai would have also avoided him as being unclean,

a Gentile,

for while his ancestors might have been Jews,

he is,

in the opinion of Temple priests,

numbered among the rag-tag people-of-the-land to the north.

He did not worship at the Temple in Zion.

He was no Jew, but rather a Gentile,

to be avoided like a tax collector or a Roman soldier.

Yet,

it is he,

Jesus tells us,

who honors the Great Commandments.

For the first quality of God is mercy

—

a word, by the way, is spoken by the Pharisee, not Jesus,

who immediately approves the lawyer by saying,

"Go, and do likewise."

The great features of our lections this week and last week

are bloodiness and death.

The Law,

as first-century Jews understood it,

commanded that these things separate us from God

in His Temple,

even from God

in His people.

Yet,

we,

turning to the conclusion of the Gospel According to St. Luke,

our text today,

understand that the God we love and worship is a bloodied

man

and,

then,

a corpse.

How moved we are to behold the devout men and women illumined

by the light of that sacred head, and that corpse

in Rembrandt's depiction of lowering the Body of Jesus from the Cross.

In the presence of this scene,

extorting our tears,

we are unimpressed with "checklist religion."

And we turn our hearts to the Psalms and the Prophets.

We read aloud today that

|

The fear of the Lord is clean. (Ps 19:9)

|

In the Psalms we find,

The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise. (Ps 51:17)

|

And in the prophet Joel, we discover,

"Yet even now," says the Lord,

"return to me with all your heart,

with fasting, with weeping, and with mourning;

and rend your hearts and not your garments.

Return to the Lord, your God,

for he is gracious and merciful" (Joel 2:12-13)

|

In these lessons,

Jesus has revealed to the Pharisee and to the world

the conclusion of Temple worship.

Astonishingly,

just a few short years hence the Temple with its altar will be razed to the ground.

All Temple sacrifice will cease ... forever.

And the new Temple,

raised up in three days,

will be a man known to all as a bloody corpse.

For the sacrifice of God is the very stuff of Heaven.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.

Amen.

The painting of the Jericho road victim

by Bertram Poole

posted on the

Hermitage website

is bathed in red and purple.

The victim is covered in red.

And

the painting posted on the Hermitage "Spiritual Conferences" page

by Aime Morot

depicts the victim as a pale, near-dead figure,

almost a corpse.

These artists

understood the horrible dilemma that was being set before the priest and the Levite

in Jesus' carefully constructed test.

If they come to the aid of this man,

they will honor the Second Great Commandment, but they will fail in the First.

In their own terms,

they will have done the ethical thing,

but in so doing,

they will have stumbled in their devotion to God.

For in touching the victim,

they will become ritually unclean,

unable

to approach the holy altar of God,

falling down in their rotation.

They will have to wait for time to restore them to cleanness

and

abrogate their appointed obligations to God.

The painting of the Jericho road victim

by Bertram Poole

posted on the

Hermitage website

is bathed in red and purple.

The victim is covered in red.

And

the painting posted on the Hermitage "Spiritual Conferences" page

by Aime Morot

depicts the victim as a pale, near-dead figure,

almost a corpse.

These artists

understood the horrible dilemma that was being set before the priest and the Levite

in Jesus' carefully constructed test.

If they come to the aid of this man,

they will honor the Second Great Commandment, but they will fail in the First.

In their own terms,

they will have done the ethical thing,

but in so doing,

they will have stumbled in their devotion to God.

For in touching the victim,

they will become ritually unclean,

unable

to approach the holy altar of God,

falling down in their rotation.

They will have to wait for time to restore them to cleanness

and

abrogate their appointed obligations to God.