Romans 2:10-16

Psalm 8:1-9

Matthew 4:25-5:12

Two weeks ago, on the great Feast of the Holy Trinity and the Descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, we meditated on a God Who is, in His Nature of Three Persons, Relationship and Who meets us, one-by-one, in relationship. With this insight we might ask, "Then, what is the role of the Church?"

Those of us who were formed by the Western Catholic Church might not see this instantly. I recall many Catholic priests along my way discouraging personal piety, discouraging personal religion, imploring the people to focus always on the corporate. The Roman Missal only recently changed "We believe" in the Nicene Creed to "I believe."

As I think of a few single-word associations with the Roman Church, these come to mind: hierarchy or rules or teachings. I used the Catechism of the [Roman] Catholic Church for adult education in the Anglo-Catholic churches I had charge of and in the Roman Catholic churches I served. And EWTN or Catholic Answers were frequented by the people around me. Why? Because for all of those who wished to know the Church and the life of the Church, here was the Rule of Life. Here was the heart of the Ecclesia.

Certainly, we are nothing and nowhere (and much worse than that) unless we embrace God's ways as our own. But from the time the Hermitage has become an Orthodox Catholic religious house, I have come to see that our Church takes very seriously St. Peter's words, "living stones built into a spiritual house" (1 Peter 2:5). Here is the foundation and essence of the Church in Holy Orthodoxy. Yes, a hierarchy exists, but when you actually meet these men with their long, white beards and grave demeanors, the atmosphere is not "CEO" or "authority figure," but rather holiness, humility, kindness. These men teach, but as holy men teach.

And what of the people? In the Orthodox Church everything is focused on the individual journey to God. This is uppermost. Each is a holy pilgrim, praying and fasting and completing his or her spiritual development, among other pilgrims. The transformation is from being humans-with-a-spark-of-divinity to divine-figures-who-retain-human-features, as Jesus has. Perhaps from time to time we look around us and notice that others are becoming more luminous as they move higher and higher up the holy mountain to the place where Moses had to wear a veil, lest others be overwhelmed by his radiance. The Church is a gathering of these radiant ones, painted on its walls as a communion of saints and gathered in a gracious company of local church members who are guided by them, indeed, are becoming them.

Two weeks ago, we celebrated the Descent of the Holy Spirit. Today, we celebrate the purpose of this all-important event, which is the ascent of the human spirit, of our imperishable souls ascending upward to their proper home, which is the Kingdom of Heaven.

At the beginning of Lent in the Orthodox tradition, an example is set before us — two saints: St. Mary of Egypt and St. Zosima of Palestine. Their story is self-consciously about this process of sanctification. Zosima is a monk who looks around him and notices that he seems to be the one who has ascended above all others on his trek up the holy mountain. He, therefore, leaves his monastery to seek other religious, to seek holy men and women. He decides to travel to the Holy Land, perhaps to join a monastery there, and then, as Lent begins, to go into the desert, the same wilderness Jesus had entered, and to fast there in preparation for Great Pascha. The desert has many monks who have departed from the monastery to fast for forty days and to encounter the evil one as they follow Jesus' earthly pilgrimage carefully and precisely. There he meets a woman who has been living as a solitary and a penitent in the wilderness for the past forty-seven years.

As St. Zosima would discover, St. Mary of Egypt, had completed a near total transformation. She had reached the point where she had diminished her human character such that her divine persons could be seen plainly. Her vision had been cleared of all worldliness. Her heart had attained purity. She was barely recognizable as a human. Her interior was nearly divine. Along the path, as her worldly thoughts and desires slowly leached out of her like inebriating poisons, she noticed that divine powers began to supplant her human capacities. She had internalized all of the Holy Scriptures and could cite any passage at will. She had the gift of prophecy, predicting the future, at least to some extent. She had the gift of omniscience, seeing other people and events from afar with perfect accuracy. She could read hearts knowing the invisible thoughts of the soul though they were well hidden. She was able to transport herself with ease over the earth, walking on water with perfect mastery. We might say that these are the attributes of an angel. More to the point, she had become more and more like the God-man, Whom she entered the wilderness nearly a half-century earlier to find. She had reached the highest degrees of sanctification. She had reached the summit of Mount Sinai, we might say. Needless, to say, St. Zosima was humbled by her, was devoted to her, and now sought to ascend higher to where she had arrived.

In her, the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church presents us with the Orthodox vision of the Church: individual, living stones built into an immaculate and radiant temple. The story of St. Mary of Egypt and St. Zosima is held before us each Lent in the Orthodox calendar because this is every pilgrim's map and journey: each of us ascending spiritually toward the Kingdom of Heaven or, better said, becoming the Kingdom of Heaven.

This marks a good starting place as, today, we honor and venerate the Russian saints. For in them we see this same dunamis or energy, which has become known as the starets tradition. The word starets means "elder," recalling a fourth-century Greek term for the same person — a wisdom figure in a monastery, or perhaps living as a solitary in a hermitage. Among the greatest of these is the nineteenth-century saint, Seraphim of Sarov (d. 1833). We cannot meditate on all the Russian saints in the time we have (remembering St. John of Shanghai and of San Francisco so close to his feast day last Sunday), but we could do worse than to devote our time this morning to St. Seraphim.

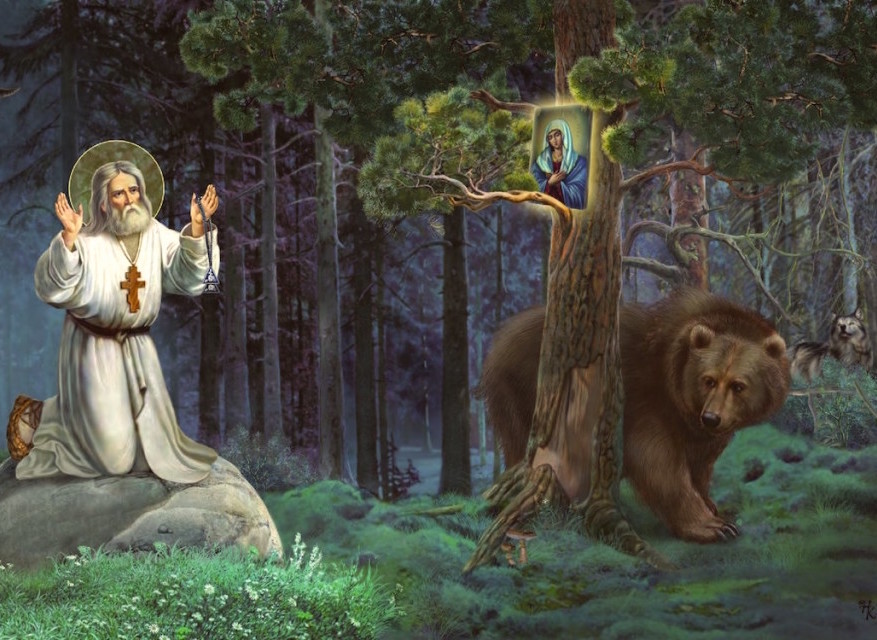

Like St. Mary of Egypt, St. Seraphim had arrived to the fullness of theosis with divine powers appearing as his human traits and thoughts were diminished. He had dominion over nature in its food-chain aspect. Famously, the enormous and fierce Kamchatka Brown Bear ate from his hand like a gentle domestic pet, who brought him honeycomb to eat at his hermitage. He had dominion over disease, healing people instantly however remote from him. He could appear at a distant bedside in a moment and then disappear again once. As the empyreal spiritual world is superior in every way to our material world of dirt and clay, so was his authority over matter and time and space. He could restore life to the dead. He could wrest the souls of the damned from the jaws of Hell. On one occasion, he admonished the sons of a man who died in grave sin: imagine how difficult it is "to tear the soul of your drunken father from the arms of Satan" (Kontzevitch, 66.)

Requiting his bold and powerful prayers, the evil one constantly assailed the great starets. And perhaps we forget that mastery over evil is not a "wave of a wand." It is not a "magic moment" of "being saved." But rather, it is a constant battle fought at great personal cost. For restless and insolent evil never relents. On one occasion, an elderly woman related,

|

A grace-filled magnetic power emanated from him. He started

drawing me to himself, but the enemy did not allow it until the Elder's prayers had strengthened beyond the enemy's resistance, then I suddenly found myself at the feet of St. Seraphim feeling an ineffable and indescribable heavenly blessedness. (Kontzevitch, 67) |

Human authority over the material world, defying the laws of physics, should not surprise us. For the world is the lesser and pathetic enemy of God. It wishes always to claim us — our attentions, our fascinations, our thoughts, and our souls — for the prince of this world (Eph 2:2), first dragging us through its dirt and soiling us, and then drawing our clay down into its nether regions, which is the unredeemed world's essence: eternal death and stinking decay. And here we encounter humankind's central equation:

| We can become all body in our pursuit of pleasure until the spark of divinity is smothered. |

| We can become all soul until the mortal coil of our flesh is nearly burned off with holy fire. |

| Blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God. |

Perhaps nothing in Russian spirituality puts people off more than this tradition of suffering, which the Russian saints call podvig. An Archimandrite of the Balaklavsky Monastery during St. Seraphim's time wrote,

|

The true monastic mantle is the indifferent bearing of cursings and slander.

Without sorrows, there is no salvation. (Kontzevitch, 71). |

But those who have fastened their eyes upon the world yearn for saints who live harmoniously with nature — in the West, a Francis of Assisi with birds alighting upon his shoulders and little deer eating from his hand. But this is more the stuff of garden center statues than of spiritual or worldly reality. The real Francis of Assisi lived a life of constant suffering, of Russian podvig. Why? Because he arrogated to live the Beatitudes, which we read once more this morning. Anyone who does this, who attempts actually to live them will be destroyed by the world.

Then, why did Jesus deliver this famous Sermon on the Mount, which depicts a life that transcends even all the other Gospel teachings? (Have you ever noticed the difference between the Beatitudes and all the rest of the Gospels?) Because He wanted us to know what Heaven was like, not earth. He wanted us to see God with a pure heart. But by that same token, He wanted us to see something very important here on earth: the ways of God are utterly incompatible with the rules of worldly life. And the one who attempts to live the Beatitudes the world will destroy ... as Francis was destroyed at a young age. We must remember that the high point of his life, his moment of greatest honor and highest attainment was to have the wounds of Christ etched into his hands and feet and side, bleeding in pain. It is suffering, which marks the saint, not prosperity ... or a kind of hippie beatitude of little creatures dancing in the forest. The forest is the place of wolves and huge, hungry bears. Yes, the saint of Assisi or of Sarov might have dominion over these but that is to remind us of the torn flesh of carnality.

In the Person of Jesus of Nazareth, humankind met with God — God, Whom we resemble, mysteriously, but Who is utterly unlike us is so many ways. The Son of God taught us to forget all worldly ambition, to put ourselves last in that respect, to practice poverty (while offering in his person an example of chastity), in fact to reject the world. For until we scrape the charms of this world from our souls, to clear the divine spark of its smothering clay, we shall never become like Him, we shall never see God. He encouraged us to walk on water and to follow Him into death: death, which is nothing more than the gate into a garden. He told us to eat His Flesh and drink His Blood, which caused hundreds or perhaps thousands to walk away from Him in disgust. As the Prologue to St. John's Gospel reminds us, human rejection would become His hallmark: "He came unto His own, and His own received Him not."

I encourage you to go back and read the Beatitudes through these new eyes, and you will see that it is, line-by-line, an antagonism between the world and Heaven until you come to the final lines that promise you will be persecuted for fixing your gaze on Heaven.

Nearly two thousand years later, rejection continues to be His hallmark while a new Jesus, more acceptable to humans is invented on the basis of ... nothing. There is nothing in the Holy Scriptures or the historical record that depicts this invented Jesus. This invented Jesus is our pal. He wants us to succeed in the world. He grants "Candyland prayers" like smart phones and shiny new cars, dream houses and six-figure salaries. He wants us to be #1 ... and our sports teams, too! More than half-a-billion people worldwide worship this invented Son of God.

Meantime, the real Son of God continues to be with us. He is Emanuel, God-with-us, and He has promised to be with us always, even until the end of the age (Mt 28:20). He beckons us to follow Him, to follow Him into divinity, into spiritual power, and into the fullness of life we see in Him.

This is the life path of the Russian saints

—

to discard the claims of the world and its elemental powers,

to suffer and to be bold in our suffering,

to complete the essential process of theosis,

diminishing our bodies

while

magnifying our souls,

even unto an ascent which brings us to the glittering radiance of the Kingdom of Heaven.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.