Isaiah 53:10-11

Psalm 33:4-22

Hebrews 4:14-16

Mark 10:35-45

|

"For the Son of man also came not to be served but to serve,

and to give his life as a ransom for many." |

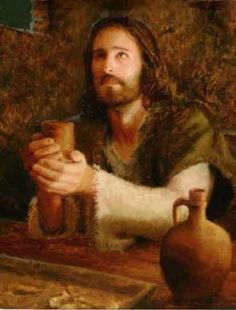

May I tell you the story of our salvation? It is the story of friendship with all the highs and lows that come with that word. It begins with God coming to pass the time with us in the cool of the day (Gen. 3:8), and it reaches a climax with the Son of God saying that we are no longer slaves, but are to be his friends (John 15:15). Most important, it touches every nerve in the human experience from our birth to our death.

God is our Father. We are His adoptive children whereby we might cry out to Him, "Abba! Father!" (Gal. 4:6, Rom. 8:15) But it is His hope that we mature, so He has sent His Son that we might "all attain ... to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ" (Eph. 4:13). Notice that we attain to maturity, not as passive creatures receiving it from God. His ideal for friendship does not render us childish or helpless. Certainly, being cared for is a cherished aspect of any relationship. Anyone who has been ill and experiencing the devotion of a spouse or a friend knows that. But should the relationship become only one of helpless patient and stolid caretaker, well, that is a very different picture. It is not a bad picture, but it is a different picture.

We attain to maturity by becoming seamlessly wedded to the commandments. We explored this in a recent reflection: to be a just woman or man, is to be trued like a spoked wheel or tuned as a harp with God's commandments being the golden source for all of our pitches. The Eastern Church teaches that to become perfectly just, perfectly tuned, is, mysteriously, to become the Lord Jesus, our exemplar — a process of conversion and transformation known as theosis.

Union with God is the goal of this journey but also unity with our brothers and sisters, who are also God's children. God has given us the experience of family to understand this, in which we begin more or less in a state of helplessness and then mature to become equals with our parents ... in a sense, but not entirely. And then in the Gospels we see Jesus expanding the definition of family to signify everyone who is tuned to Heaven's pitch: ".... whoever does the will of my Father in Heaven is my brother, and sister, and mother" (Mt 12:50).

But we do not live in Heaven. God must speak to us in our own language and in our own culture. It follows that to understand God's actions among first-century people, that we must also learn about the cultures and stories of first-century Mediterranean countries. For this was the stuff that God used in His own art in order to move the hearts of humans.

As one great example, let us consider the Cross. In our time it is a cultural reference that has become universal. Make the sign of Cross anywhere, and you will be understood. But why the Cross? And why did God enter history in the obscure town of Nazareth, for that matter? Both were suggested to God by Jewish culture. In the year 4 B.C., following a mass revolt in Sepphoris (three miles from Nazareth), the Roman General Varus ordered the crucifixion of 2,000 Jews, their families being slaughtered at the foot of their crosses in the sight of these condemned men. No symbol could surpass the Cross to enshrine the ancient Jewish world's sorrow or its brokenness. No symbol could surpass the Cross to convey the world's utter hopelessness and captivity. And no other symbol had been proposed by Jewish culture that could capture this brokenness. It was the Cross upon which Jesus would ascend, expressing both the world's brokenness and the depths of God's love. Here we have the example par excellence of the truth that "Man proposes, but God disposes." ("Homo proponit, sed Deus disponit." Thomas a Kempis, Book I, chapter 19, The Imitation of Christ).

St. Paul followed God's example by attempting to reach every human heart through local culture: "I have become all things to all men" (1 Cor. 9:22). Through local stories, references, and idioms, Paul becomes "one" with his audience. The path he followed drew an arc on the map from the Holy Land to Asia Minor then along the northern shore of the Mediterranean to Macedonia and Greece thence to Italy, Gaul (France), and Iberia (Spain). And he was mightily helped by the fact that this lifeworld spoke one language: Greek, following the conquests of Alexander the Great (b. 356 B.C.). We know that Jesus and His Disciples spoke Greek, for their quotations of Sacred Scripture are from the Greek translation of the Bible, not from the Hebrew Scriptures. St. Paul spoke Greek, wrote all his letters in Greek, and undoubtedly preached in Greek everywhere he went. Recent archaeological research suggests that the language spoken in Rome was Greek, suggesting that Latin was something of a Roman aristocratic observance, spoken by the First Families of Rome, in the Senate, and on solemn occasions of state.

Naturally, the stories of Greek culture also circulated freely through this lifeworld as a kind of common treasury of sayings and references. Among the highest ideals of this Greek, or Hellenic, culture was the category of philos, or friendship. Not the casual relationship we know today, but something far deeper. We find it permeating Homer's epic writings, Aeschylus' tragedies, and is examined as a primary topic of Greek philosophy. Moreover, as the Greeks understood that the point of life and purpose of the city-state were to make men and women better that they might attain to their highest goods, so friendship was a primary instrument in a self-giving love intended to bring the other to his or her highest or most virtuous state of mind and soul. In first-century Rome, Cicero wrote that amicitia, friendship, was the highest species of love on earth. The great philosopher Pythagoras taught that friendship was the perfection of human relationship. Friendship was the soul-enlivening affinity between people that separated humans from the beasts, that elevated a wife from being a servant to a soul mate, and that any human bonds of friendship that did not follow this ideal were shackles, the mark of the slave. All of this clarifies how Jesus' culture understood Him when He said, "No longer do I call you servants,... but I have called you friends" (John 15:15).

A story written to express the Pythagorean ideal of friendship circulated widely in Jesus' time. It described two pupils of Pythagoras, Damon and Pythias, who had entered this high ideal of philos, or friendship. The story also included another ideal, a negative one: the tyrant, Dionysius I of Syracuse, whom the ancient world deemed the worst of all rulers. He was the ideal of the worst of any ruler.

As the story unfolds, Pythias was accused of plotting the overthrow of Dionysius. He was arrested, and sentenced to death. Accepting his sentence, Pythias asked the tyrant if he might first go home, settle his affairs, and bid goodbye to his family. This the king refused .... until Pythias' friend, Damon, offered himself as a temporary ransom until Pythias could return. When the day of execution came, Pythias was nowhere to be seen, and Damon was taken to the place of beheading. At the last minute Pythias appeared explaining that pirates had overtaken his ship and that he had escaped, then swimming for his life that Damon might be spared the fate that was properly his. The tyrant Dionysius was so moved by this show of friendship that he released them both. Later, he sought to enter these bonds of friendship with Damon and Pythias but was refused, for friendship could not be decided this way, but was a matter of mutual attunement and personal discipline.

The story was universally shared in Jesus' time. In the sparely written Acts of the Apostles, where we find few sidelights, St. Luke chooses to mention a small detail on the ship that would carry them to Syracuse: a carving on the ship's prow, Twin Boys (Acts 28:11), a clear reference to the soul mates of Syracuse who represented the ideal of friendship. Why would he single out this detail (in a story having no "small talk"). Because, no doubt, the early Christians, following Jesus' pronouncement on friendship (loving Him and loving each other), saw themselves in precisely this light: noble friendship having permanent, even Heavenly, bonds. Repeatedly these friends risk their lives as a show of that love.

In this culture, friendship signified a soul-to-soul relationship, a very deep form of mutual understanding, respect, regard with the aim of helping the friend attain to his or her highest virtue, which we today call conversion to Christ. And it was the relationship that begins our story as God's children: as God is revealed to be our friend, conversing with us, that is, with Adam and Eve, in the cool of the day (Gen 3:8).

Friendship can be a hard road.

Sometimes our friends do not pursue the

highest good.

They drink too much.

They gamble.

They get caught up in unworthy pastimes.

What is a friend to do?

We look for ways to stir them,

to wake them up,

to shock them into taking hold of themselves.

This was the case of God's beloved human creatures

who had become lost in sin

and

had forgot even what friendship with God was.

As the Early Church Fathers would say,

we had forgot where we were going;

we had forgot who we were or what we were supposed to be.

We had become like dull slugs of silver

instead of newly minted coins bearing an imperial face.

And this brings us to the Advent of Christ,

who would show us the true image of men and women,

and

from this example the coin would be restruck

that

we might reclaim our royal image.

For a thousand years, all of this formed the Christian theology of salvation: friendship with God solemnized in adoption. Yet, a thousand years ago this theology took an unexpected "left turn." An Italian monk, Anselmo d'Aosta, invented a new idea expressed in a super-rarefied logic. Within the tiny wheels of these inner clock-workings, Anselmo had worked out a speculation that transmuted God from being a faithful and loving Father, to the new figure of a bloody tyrant. Thousands of years after Adam and Eve's expulsion from the Garden and out of the mists appears this angry God who suddenly and unexpectedly demands payment for a debt. It would be as if we had received a bill in the mail for billions of dollars concerning a house which a distant ancestor had lost in bankruptcy ... and, we might add, contravening the Old Testament statutes concerning amnesty, jubilee, the forgiveness of old debts (Deut. 15:1). Anselmo's God is in a state of rage. He is implacable. He cannot be appeased. It was not enough that Adam and Eve were evicted from their home long ago, but now we see God depicted as a landlord demanding back rent from their descendants and with compounded interest. Failure to pay brings a penalty: death. But they cannot pay, so a pound of flesh must be extracted ... or roughly 185 pounds of flesh, the bloodied flesh of Jesus of Nazareth. This God says, "That will satisfy the debt! This man will go to the Cross!"

This new, invented conception of God as an angry landlord demanding blood should have repelled Anselmo's contemporaries, but it did not. What happened, they might have asked, to the merciful God we find throughout the Old Testament? Where is the God Who says,

|

"Fear not, for I have redeemed you;

I have called you by name, You are mine. When you pass through the waters I will be with you; and through the rivers, they shall not overwhelm you; when you walk through fire you shall not be burned, and the flame shall not consume you. For I Am the Lord your God, the Holy One ..." (Isaiah 43:1-3) |

How or why Anselmo's theological speculation caught on — written by an Italian monk a thousand years after universal acceptance of sacred theology — I cannot say. But these were heady times for the Roman Church, for it had just splintered off from the ancient Catholic Church as a separate entity a few years earlier, and it seemed bent on writing new theologies for a new age, new philosophies for a new Church. Perhaps it was this novelty — of the Roman Church having its own theology distinct from the ancient Catholic Church — which propelled acceptance of Anselmo's new idea. Certainly, the next Christian splinter group, the Protestant Reformers, became enamored of Anselmo's theology making it the set piece and center of their own theological writings. But please understand that this bloody tale is very different from the noble theology that preceded it for a thousand years.

The Greek Fathers understood the Advent of Christ in terms of a friend's faithfulness, even in the face of death. The emphasis was not on the bond or even on the bloody death. The focus was entirely on the nobility of friendship. True to the tenor of the Scriptures, Father God had kept faith with us though our conduct had not been worthy of His friendship. Indeed, this is the summary of the entire Hebrew Bible: a faithful God being devoted to an unfaithful people. But watching the descent and degradation of His friends became too much for Him, so He sent His Son to befriend us, to teach us, to bestir our hearts and souls to return to ourselves and to this noble friendship. Is not this the story that Jesus tells us? Of the kindly vineyard owner and his rebellious tenant-farmers?

|

... and the tenants took his servants and beat one, killed another,

and stoned another. Again he sent other servants, more than the first; and they did the same to them. Afterward he sent his son to them, saying, "They will respect my son." (Matthew 21:35-37) |

In terms of our salvation, Father God sees the chaos of sin that besets the world and understands that humankind has not only strayed into the wood of error but now does not even know what the destination was to be in the first place. So He sends His Son that in Him we might see the destination: excellence of the human mind and soul, the highest good, the virtuous life, recommencing our journey toward God, Who is the only good (Mark 10:18).

God's Son would shake us out of our deadly slumbers, would call us back to ourselves. And what is this moving drama that will bestir the human heart and bring grown men to tears? It is the image of an innocent and blameless man giving himself as a ransom for his friend: Damon for Pythias. It is the image of a man engaged in hand-to-hand combat with pirates, so he could swim for all his worth, so he could give himself as a ransom for his friend: Pythias for Damon. Here is humanity in all its nobility. Here is true friendship. And here is the story of God and His Son, Jesus, the story we knew for a thousand years: a ransom not just for one, but for many. The royal vineyard Owner in his infinite patience and love has sent the Heir. He has come to show us who and what we are and where we are bound. And He tells us at the climax of the drama,

|

"Greater love hath no man than this,

that a man lay down his life for his friends" (John 15:13). |