Amos 8:4-7

Psalm 113:1-8

1 Timothy 2:1-8

Luke 16:1-13

Did you know that all literature is an echoing song? Read Shakespeare, and you will find countless references to the Holy Scriptures. Or read Thomas Hardy, and you will find Milton's phrases and sentences as well as those of Shakespeare, and Holy Scripture. This is not the petty theft of comely words but rather the way literature itself functions. The mention of a few words has the power to light up whole complexes of themes and emotions from other works -- layers upon layers, giving depth and dimension with great efficiency. One or two words might set fire to hearts who knew these old conflagrations intimately: "Hector is dead. And there is a light in Troy."

We hear that same echoing song running through Jesus' sentences and phrases, too. When He says, "Who has ears let him hear," he invokes Isaiah and Jeremiah summoning not only the emotional content of those passages from the Prophets but also lending a sense of history to the long, winding narrative of God's unfaithful people. When Jesus hangs upon the Cross saying, "My God, My God, why hast Thou ...," he is expressing not simply personal sorrow or despair but rather invokes the entirety of Psalm 22, which has a more ambitious programme in mind than grief.

During the five-hundred-year era of printed books, we have become familiar with subtexts, pretexts, and intertexts. Readers underline these sentences or bracket whole paragraphs. They are the building blocks of literature. But in Jesus time, the deep and rich streams of inter-literary expression flowed far more readily, for the human voice and the human spirit were the printing presses and internet of the day, and these currents carried ripples of repetition that everyone would instantly recognize: "There was a man who had two sons. The younger wanted his inheritance now ..." or "There was a great king who sent out invitations to the wedding feast of his son ..."

Don't be fooled by Scripture scholars and professional exegetes of recent centuries who have buried themselves under the debris their own charts and arrows pointing to imaginary manuscripts. (Many of these scholars are still chasing after a first-century book, the Q Source, that never existed!) No. The Iliad, the Odyssey, Gilgamesh, and the Sacred Scriptures themselves stand as monumental counterexamples to such mirages. These oral epics form a tradition that dominated first-century Palestine and, indeed, has come down to us today with their majesty and power. Think about it. The Pharisees, Sadducees, and Scribes that thickly populate the Gospels are constantly quoting and arguing points of literature though no one present held a single book in his hand.

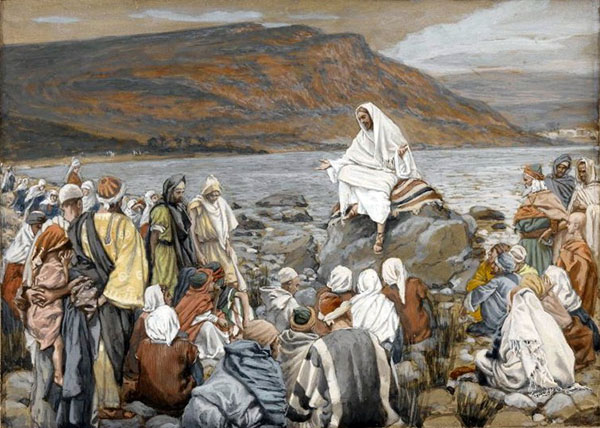

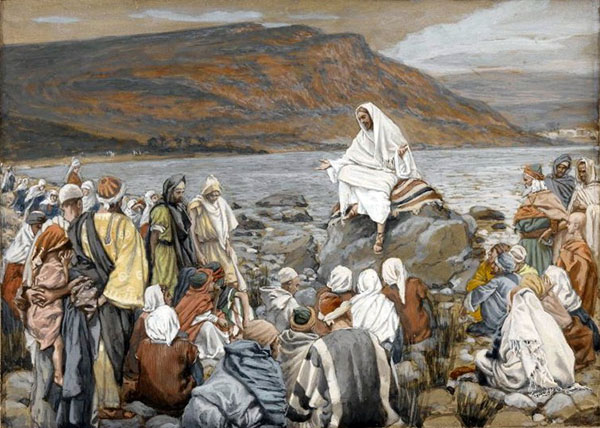

Jesus went from town to town explicating and elucidating sacred texts, too. And, of course, the Holy Gospel itself was constantly proceeding from His sacred breath. We may be sure that for three years, He journeyed all over the Eastern Mediterranean region and that His disciples and camp-followers heard the same the parables again and again. Those whom He visited -- who heard Him upon hillsides, speaking from boats moored just offshore, or perhaps standing before them in their own synagogues -- would hear one parable today and then another several months later, which might use its predecessor as part of the echoing song that Jesus intended lending depth or perhaps irony to His homilies.

Reading the a Holy Gospel in book form does communicate the dimension of time as any book does. First this happened, then that. But it does not capture the multiple layers of time represented by Jesus' repeated visits, for phrases cherished from past visits still ring in the ears of his audience today. Without benefit of this, we might struggle with readings like the one have today in St. Luke's Gospel. Does Jesus really praise the evil steward for his shrewd business practices? In recent years, I have heard worldly bishop's laugh in their homilies saying, "Ya know, you really have to hand it to that clever steward!"

We would avoid these pitfalls if we held in mind the oral literary culture in which Jesus worked and the methods he used to move the hearts of His listeners. Consider the bare bones of today's story, and we will see the Master at work. There is a master who has two debtors who are to be forgiven their debts. "Wait a minute," we hear one man in the audience say to another. "Didn't we hear this parable the last time He was here? 'Simon, I have something to say to say to you ... there was a certain creditor which had two debtors: one owed five hundred denarii, and the other fifty." "Yes," the other replies. "And I seem to recall another parable He told last year. It ended, "To whomsoever much is given, of him shall much be required." These two men are on to something.

Jesus has set the scene. In His earlier homilies, the meaning is obvious. He is not talking about worldly reward, but of ultimate outcomes. The Master in His earlier parable is God. The ones who owe Him what they cannot pay are all of us. The contrition and gratitude we offer on the occasion of this, our forgiveness, is nothing less than eternal salvation. The boundaries around this story are incommensurables, to borrow von Balthasar's phrase, and they are as dependable as God Himself.

The second tale is told with the first as its backdrop. In the latter version, the evil steward stands in for the Master. He will forgive these debts. His debtors will enter into bonds of eternal gratitude according to the scheme that the steward imagines. We the listeners are able to compare these flimsy transactions to the Heavenly version. Certainly, the evil steward cannot expect the same reward as the children of light, who, we learn, are inept in worldly dealings, but will he receive even his earthly reward? The comparison of the two parables of itself suggests the preposterousness of the scheme, fitting fare for those who imagine there is honor among thieves. And no one present would be unfamiliar with the passages in Amos: fixed scales, skimmed epahs, and increased shekels.

The final sentence makes the meaning clear -- choose today, who has ears, you cannot serve both Mammon and God. And, no doubt, those listening will be reminded of yet another parable of Jesus: "store not your treasure where moth and rust corrupt ...."

Without ever saying it, in today's parable Jesus has pointed to the greater life defining it by its poor counterfeit, a broken world that vainly attempts to prop up its own poor versions of safety and security. In this perspective, the meaning is clear: the clever steward is whistling past the graveyard ... where his own grave even now is being dug. Finally, a greater theme, one that Jesus revisits time and again, comes into view: the Holy Scriptures are not the story of a faithful people, but of a faithful God. He alone might be trusted with your future and your life.