Exodus 32:7-14

Psalm 51:3-19

1 Timothy 1:12-17

Luke 15:1-32

Undoubtedly, tens of millions of people sitting in church this morning will hear about the lost being found, about contrition and repentance, about reconciliation. To be sure, these are strands that we find in our lectionary readings today. But what exactly do these things mean? What is reconciliation? To what or whom are we being reconciled? For now let us say, "to wholeness." I believe that this is just what Jesus has in mind with these three parables.

You know the ancient principle, going back at least as far as Origen, that Scripture glosses Scripture, so let's see how each of these parables makes clear the meaning of the others. But first let me ask you: Have you ever misplaced a twenty-dollar bill? First, you are startled that it is gone. Did it fall out of your pocket in the car? Is it stuffed in a pocket of your dungarees? Where the dickens did it go?! And you will not rest until you find it. A friend might say, "Hey, get over it! It is only twenty dollars, and you have much more than that in the bank!" But that is not the point. Only an hour ago, everything was right. And now everything is not right. It is not about the twenty dollars really. You simply want to restore the wholeness that had been yours only a short time ago. And this is the meaning of the lost coin. The real purpose for Jesus is to set up the parable of the one lost sheep.

Would a prudent shepherd really leave his flock to find one lost sheep? Not in Newark, New Jersey he wouldn't, to take one example. For upon his return, he would be greeted with the smell of one, great-big lamb roast barbecue in Freylinghausen Park! But the loss of this lamb is not about a small loss balanced against the security of the whole portfolio. It is not really about the one lamb. It is about restoring wholeness to the flock. And in the case of a lost sinner, it is about restoring wholeness to the world.

But why should it matter? In today's readings, we find Israel rebelling against God in the wilderness once again. This time they have made their own gods and have sunk into general depravity. Do you know what happens when you get rid of God? Why once God is dropped from the equation, His morality goes with Him. Why else should people not break taboos? Even extreme ones? This is human nature and always has been. If you do not believe that, then consider the culture that presently surrounds you.

At another level, why should God care whether His human creatures are depraved or whether they should or shouldn't worship a little metal statue? Do you really care, for example, that just outside our church a swarm of ants is carrying off a centipede? If we humans are all maggots, as we heard Bildad the Shuhite propose this morning in our Office lesson, then why should God care about us at all? The answer to this question goes to the heart of a greater question: What is the purpose of life anyway? I would have a most audacious statement to make: "Christian life, indeed all of human life, is ordered to one end -- that each of us become like God." God created us to be with Him, and to enjoy a fellowship of free heart and spirit with Him. You see, among the Divine attributes are an aptitude and need to love and an aptitude and need to be loved. He saw that His own essence was closely allied to pure creativity -- the fullest freedom to conceive and create with limitation. By contrast, He might have created little doll robots that looked just like Him, saying "Our Father Who art in Heaven ..." but what sort of fellowship would that be? Pretty lonely, I'd say, and, at length, perverse and pointless. No, freedom must be the essential property if His human creatures are to be like Him. They would progress, look within themselves, see their goodness and creative powers, and become true fellows, friends of God.

But this is not how things worked out. Eden is the first depiction of this freedom, and God saw that His human creature perceived his own need for another human fellow, Eve. And this was a godlike choice. Adam chose for love and fellowship, just as His creator had. But, in time, human freedom rejected God, for claiming the knowledge of Good and Evil, which the tree signified, is to become the decider of morality: what is right and what is wrong. This decision did not include becoming God in the sense of entering into His wholeness, but rather to become independent gods in His stead. Funny thing ... how idolatry and depravity always seem to go together.

Over time, the humans developed further and further from godliness, and He decided to begin again with new human creatures whose hearts were more like His. But this creation, after the Flood, also went awry. Next, He gave them Law to show them how to live holy lives that would lead more surely to Himself. Finally, He sent His Son to show them what humans were supposed to be like, what they looked like, that they might enter into the at-one-ness with the Father that Jesus described. Jesus, we learned, was our brother, and God was our Father. We were to be His children by adoption, the children of God. We would enter into the wholeness that God alone is. And all of this prepares us to hear the third parable.

Many have noticed that the Parable of the Prodigal Son is about theosis, the spiritual progression that leads through spiritual journey into the "God state," and thence to true unity with God. Fr. Henry Nouwen wrote that so many of us begin as the younger son. We are headstrong and selfish. We will accept advice from no one. And we quickly become absorbed by pleasure-seeking, getting stoned and then looking not for marriage, but rather a never-ending train of "hook-ups." Who does not hit bottom following this path of depravity?!

Next, we become the older son. We are steadfast in our love, and we are sober. We are obedient, practicing a regular life of spiritual discipline, and humble, asking nothing for ourselves but rather seeking unity with those around us. Yet, during this stage of our development we are apt to let our inner righteousness express itself in public condemnation. Having learned to love justice, we can become highly sensitized to those who flaunt the rules of decency and rightness.

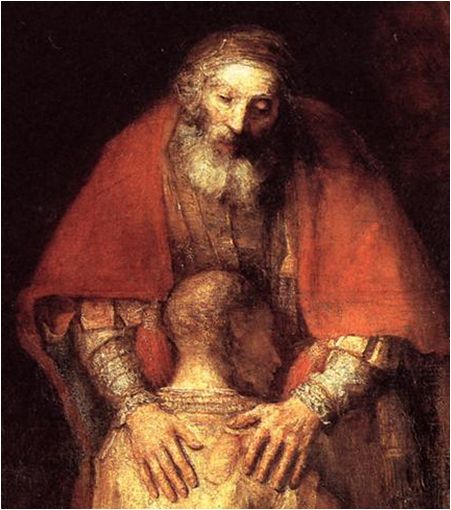

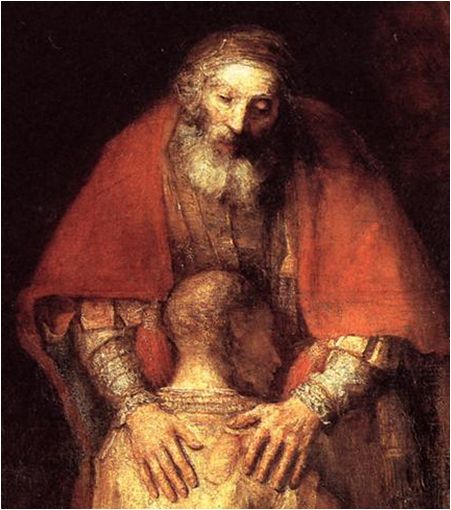

The goal, finally, is to become the father. In him is all goodness. Like Father God, He is slow to anger but swift to bless. He does not hunt his son down in brothels and taverns in order to save him, but rather remains aloof in his splendid serenity. He contains all things within him, expressed by the Rembrandt portrait which depicts him with one masculine hand and one feminine hand (as Fr. Nouwen has noticed). He watches from afar in a divine passivity, yet responds quickly with love seeing the first signs of contrition.

The story depicts with a moving graciousness our own experiences of God. When through an act of self-destructive willfulness we have separated ourselves from God, then we are separated. Period. He will not chase after or retrieve us. He will not enjoin us to follow His commands or walk in His holy ways. Yet He is always there awaiting our words of contrition, which will lead toward restored wholeness with and through Him. For it His wholeness that He wants.

Could I close by asking you a question? Whom does Moses meet with on Mount Sinai? With whom does Moses wheedle and negotiate like a deft courtier standing before a mighty and fiery king, more like an ancient Irish chieftain-king than the aloof Holy One. Surely, it is not Father God. For the Father is perfect in His serenity and does not shift from emotion to emotion in His great heart. No. For to say so would be to commit to the grave heresy of Sabellianism, or modalism, as it is known in the Eastern Church, or Patripassianism, as it is known in the West. The Latin here means that the Father does not suffer. Nor is He subject to the same upheavals of emotion that humans are.

Did you know that our God is partly human? Well, you know that God is changeless, and you know that Jesus Christ is fully human and fully God. We must come to the conclusion that our God, the Holy Trinity, is partly human. And I can hear Him grieving, pouring out His great and noble heart before Moses: "They have too soon turned away from the path that I pointed out to them. They have become depraved. Let them alone that my wrath may blaze up against them and consume them!" Oh, wait a moment! I know this voice! I have heard it! "They shall be thrown into the outer darkness!" "There shall be wailing and gnashing of teeth!" "They shall be consigned to unquenchable fire!" It is the flinty and fiery Jesus! It is the Son of God! And I hear Him weeping and grieving for us ... even as His great heart turns, like any human heart, to love us and restore us to the noble love for which we were made. It is Jesus, and He yearns for the wholeness of His flock, for we are the sheep of His hand and the lambs of His flock. More than that: we are His brothers and sisters made in the image of His Father. In that sense, wholeness in the Trinity is some mysterious way participates in the wholeness of each human life, infinitely valuable and absolutely sacred. Or as St. Paul has written, we are parts of one Body, each indispensable in its way, and that Body is Christ, and, therefore, is God, which is Wholeness itself. Amen.