Exodus 17:3-7

Exodus 17:3-7

Psalm 95:1-9

Romans 5:1-8

John 4:5-42

Exodus 17:3-7

Exodus 17:3-7

Psalm 95:1-9

Romans 5:1-8

John 4:5-42

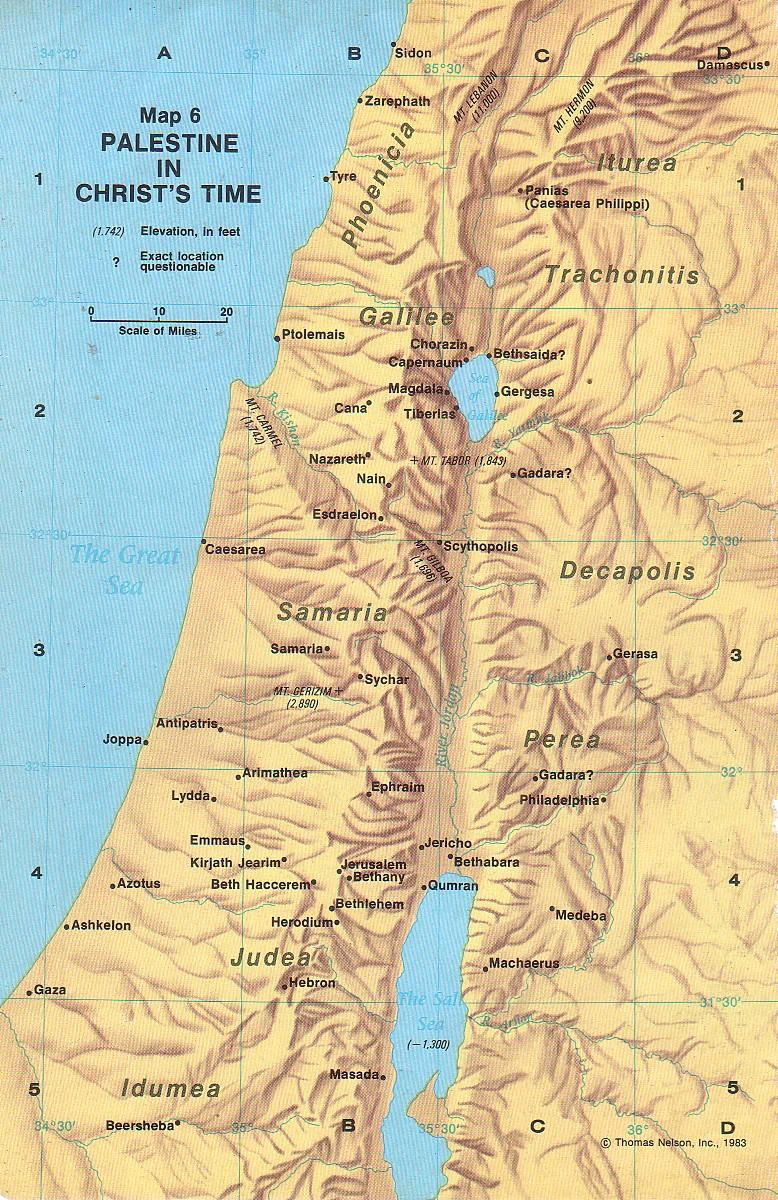

I stumbled as I read. I could not see what was really happening within the frame of these holy snapshots, offered in every paragraph of the Sacred Scriptures, precious windows into our sacred text. My impoverished imagination could not penetrate the veil of distance and time. And then a blessing came: a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In a nonce, much of what was hidden became brilliantly clear, and I leapt forward in understanding the infinitely valuable gift from God that we call "the Bible."

Not least among these was something of greatest importance to those who lived in first-century Judea, Samaria, and its environs: water. The central importance of water to the lifeworld of first-century Palestine had not dominated my mind and imagination as it should have. Certainly, it dominates the Holy Land, which a study in contrast of two great forces: barrenness and water. When I read 1 Kings, for example, I failed to see the backdrop for Elijah's confrontation with the Baal prophets. The backstory for it is drought and therefore famine, but the visual background, which all present saw on top of Mt. Carmel, was a vast expanse of water that dominated everything else, the horizon of the Mediterranean Sea beheld from a mountain's summit. (Mt. Carmel fronts the cost.) The sea — the waters that God alone could conquer and God alone can govern and God alone can give. Water.

When I read the Sermon on the Mount, I failed to realize that the multitude were seated in a natural amphitheater forming a horseshoe that faced the Sea of Galilee. Jesus naturally would have been addressing the assembled and seated people standing upon the shore. There would have been only two things set on that natural stage for the multitude to see: a great expanse of water, which is life, and the Lord of Life standing almost upon it. Indeed, Jesus often stood in a little boat just offshore, so He could preach to the crowds that tried to mob Him.

The Holy Land itself is an allegory of water and a compelling story of life being poured out onto a landscape of death,

for Palestine is a finger of arid waste set beside a salt sea if not for the Jordan River.

A vein of life opens in the north as the headwaters of the Jordan are literally springing from the earth.

Standing in these mists, one forgets about the heat and barren wastes to the south;

one is distracted from the intense, throbbing anger of Jerusalem,

seething in the first century as it does today.

Here, one is filled from within by drinking from the abundance of these springs and cooled from without as the fresh mists envelope you;

all thoughts of strife lift like a bad vapor.

It would be in this place that Jesus would ask the Twelve,

"Who do you say that I am?"

And nearby He would reveal His divine identity on the Mount of Transfiguration.

The headwaters of the Jordan constitute a locus amoenus,

a safe and pleasant place where truth is revealed in recollection and retreat.

A vein of life opens in the north as the headwaters of the Jordan are literally springing from the earth.

Standing in these mists, one forgets about the heat and barren wastes to the south;

one is distracted from the intense, throbbing anger of Jerusalem,

seething in the first century as it does today.

Here, one is filled from within by drinking from the abundance of these springs and cooled from without as the fresh mists envelope you;

all thoughts of strife lift like a bad vapor.

It would be in this place that Jesus would ask the Twelve,

"Who do you say that I am?"

And nearby He would reveal His divine identity on the Mount of Transfiguration.

The headwaters of the Jordan constitute a locus amoenus,

a safe and pleasant place where truth is revealed in recollection and retreat.

To the south flows the nascent River Jordan collecting, almost immediately, into a large basin called the Sea of Galilee (among several other names). Here, is a center of life surrounded by green hills, where Jesus' three-year ministry would play out: from the calling of the Twelve to the Risen Christ seated by the shore at dawn. In stark contrast to the rest of first-century Palestine, this basin and the hills surrounding it form a kind of "navel of the world," fertile and well fed. And Jesus would be its Lord, walking upon it, preaching before it, ordering fishes to leap toward two boats until they nearly sank, and ruling it, with its winds, to bow down before Him in reverence. Truly, this rich world and its Lord can be summed up in one word: gift.

Flowing from the south of this basin is the Jordan River in which so many have been baptized over the past two thousand years. Along this stretch, we might say, the trial of life unfolds. Opportunities arise to be baptized and to be forgiven for one's sins, to know the salvation of God, and to follow this giver of miraculous gifts .... or to trudge forward through a wasteland relying only on one's own powers or upon the unsteady support of others, and thence to a lifeless sea to the south, aptly named the Dead Sea. The Holy Land is a map and landscape of life or death. Near the Jordan's headwaters, we are asked that most important question of our lifetime, "Who do you say that He is?" He is really and truly God. On the mountain where the Son is revealed, His Father commands us, "Listen to Him!" We will have three years to meet with Him, to taste and see that the Lord is good, to be refreshed and restored unto our very souls, even to follow Him and enter the Kingdom of Heaven with the wonder and heart of a child.

But an interval is offered. An expiration date is set. We must "seek the Lord while He will be found." Harden not your hearts. For rejecting Him brings with it its own life and world. In his landmark book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell writes that to refuse the call from God is to enter a barren wasteland. Where once your life had been a verdant garden of endless possibilities, it now transforms to a desolate waste. Refusing Him, we press on through this landscape of alienation seeking comfort and "meaning" wherever we can find it. Most seek consolation in illicit sex with its false promise of spiritual intimacy and its unmistakable hallmark of cheapness as if the heart would not be hurt or the soul would not be gravely injured. Yet, we go forward carrying the weight of our dying bodies, attempting to fill ourselves with grace, which we cannot hold in a soul riddled with cracks. "We have this treasure in clay jars" (2 Cor 4:7), St. Paul writes. But only a clay that is healed may retain this empyreal treasure.

The life of alienation ends with us trudging across a blasted and cracked ground, carrying our burdens without promise of relief, and facing a setting sun. Jesus enters the village of Sychar in Samaria, at 6 P.M. Once a glorious kingdom, Israel's zenith is now well behind it. Here, He meets an old woman who knows this world's disappointments well enough. She is many times a cast-out and a pariah. She is divorced from God as the Samaritan Temple at Mt. Gerazim had been destroyed by Judeans two centuries earlier. She is shunned by Jews, for no Jew would even look upon her, much less speak, to a Samaritan. And her personal life is a vessel of brokenness. It has been lived going from one man to the next, and now living with a man who refuses to marry her. We may well imagine that the clay jar, which she always carries, is worn and cracked. And her days are spent making many trips to a well that will never fill her emptiness nor cleanse her from the stains she longs to erase.

Then, the Lord of Life appears. He offers living water. He bids her draw near to Him. With great skill, He lances her long-time boil leading her into a confession of sin. Her sincere contrition is obvious: "Sir, I would have this living water alway." And she moves from the private place of confession to the public square of corporate life announcing to all that her old life is ended, and a new life begins — a life of acceptance, of approval, and of decent love. And her burden she lays down. As we read in the Gospel this morning, "... the woman left her water jar" behind. We may be sure that she never returns to collect its chipped and cracked remains. And the people of Samaria "said to the woman, 'It is no longer because of your words that we believe, for we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this is indeed the Savior of the world.'" They too have received the gift signified by the headwaters of the Jordan: springs of living water that can never fail.

Upon the Cross, our Savior dies as a human and will conquer death as the God, Who He is. And in His humanity, broken for our sake, He voices our collective emptiness and unquenchable need: "I thirst", He cries. We rush to Him with all that we have, which sadly is nothing, for our fate is to bring Him always our needs. Again He says, "I thirst. I thirst." He is calling to each of us, for we are the creatures whom He has made and, whom, mysteriously, He loves so well. "I thirst," He cries seeking our faithfulness and, yes, our complete and devoted and unstained love. Seek Him while He will be found. Harden not your hearts. For He alone bears the gift of living water.

In the Name of the Father and the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.